THERE WAS AT LEAST one major advantage in holding a world's fair in San Francisco so close on the heels of the Chicago Exposition: many national and foreign exhibitors were persuaded to ship their treasures to the West Coast for another six months of exhibition before returning home. Because the Midwinter Fair organizers could make arrangements with prospective exhibitors in Chicago without having to travel or correspond with foreign governments around the globe, the task of lining up participants was vastly easier. Exhibits, commissioners, concessions-all could be sent to California with a minimum of fuss. The net result was that the Commissioners of the Midwinter Fair could lay before the public a sizable representation of world culture. Art and artifacts, industrial exhibits and exotic amusement concessions -- a treasure that had taken Chicago some years to assemble -- all were there in Golden Gate Park for San Franciscans to contemplate and admire from January to July of 1894.

Another real advantage -- one that the Midwinter Fair managers played up for all it was worth -- was the mild climate of the city during the winter months. Ironically, though, a severe snowstorm in the Sierra mountains delayed the arrival of the exhibits from Chicago, so the opening date of the Midwinter Exposition had to be postponed almost four weeks. But once the exhibits arrived, the climate of San Francisco more than compensated for the Sierra blizzards. The mild temperature and verdant winter landscape mightily impressed visitors from the Midwest and East Coast. To see a section of the country that turned green in winter must have been a revelation to visitors from Minnesota or Vermont, Paris or Moscow. Indeed, the heavy migration to San Francisco during the last several years of the nineteenth century might be attributable to the reputation that California had acquired as a veritable Eden in all seasons. Between 1890 and 1900, San Francisco's population jumped from 300,000 to well over400,000 inhabitants. The theme of "Benign Abundance" featured so prominently at the fair must certainly have had some part in drawing those newcomers to the city.

In local exhibits, Californians capitalized on the natural advantages of their state, and the colorful history that Bret Harte had popularized in his gold rush stories. One exhibit showed the excitement of the gold rush days, and even gave visitors a chance to be held up at gunpoint (all in fun, of course) during a stagecoach ride. Or mostly fun: on one occasion, the stagecoach overturned, injuring several passengers, thereby giving them a real taste of the actual perils of stagecoach travel in California.

The Viticulture Building, whose entrance was a gigantic oak barrel, had an interior designed like a traditional German Weinstube with vine-covered rafters, large written inscriptions on the wooden walls of the tasting room, and plaster casts of Bacchus and Mercury. Its shelves featured the finest wines from throughout the world, including such California vineyards as Inglenook, Cresta Blanca and Haraszthy. Indeed, over three dozen local wineries had displays. Several of these vintages won awards, making a powerful statement about California's challenge to European vintners.

THE VITICULTURE BUILDING AT THE EXPOSITION

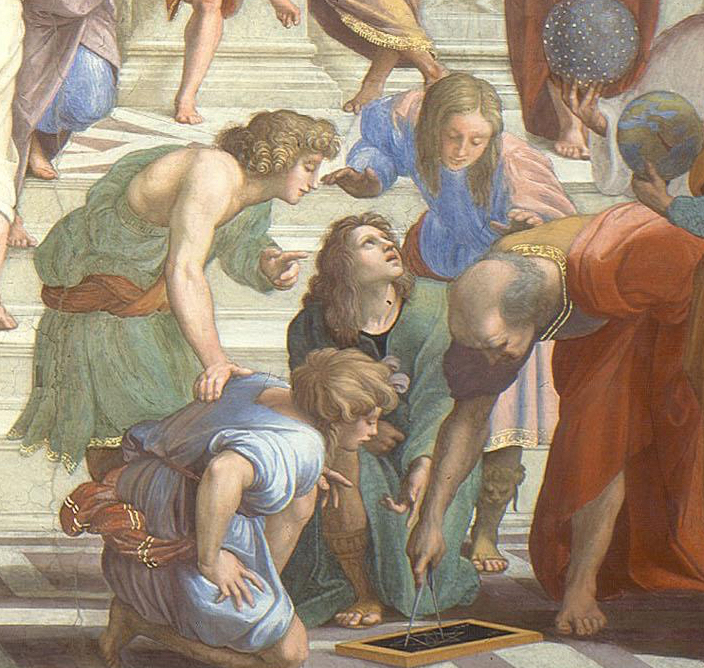

Another exhibit showed off local vintages, and dared European wine makers to match the quality of California wines. "Only second to her mines/ Are California's vines," ran the adage of California growers. Inside the Viticulture Building the visitor could contemplate a contemporary engraving that showed an aged man representing Europe, his head wreathed with a circlet of grape leaves, accompanied by a cavorting faun. His head is bowed and in his right arm he holds a thyrsus, the symbolic staff carried by Bacchus, god of wine. He is surrendering the thyrsus to a young man accompanied by a lady clothed in an American flag. The lady is America, the young man is California. It is the destiny of the young state, the artist implies, to inherit the great tradition of wine-growing from a tired and aging Europe. There is no record of whatEuropean visitors to the Viticulture Building thought of this brazen presumption. But the intention on the part of the Exposition Commissioners is clear. The engraving and the Viticulture Building itself were unmistakable announcements that California fully intended to become a major wine-producing state. And, in the course of the succeeding years, so it did, increasing from the 17 million gallons of the 1890s to 400 million gallons in the year 2015.

EUROPE PASSES THE THYRSUS TO AMERICA

Exposition buildings housed some truly whimsical manifestations of local pride. There was a gigantic elephant, a gift of Los Angeles, fashioned from half a tons worth of walnuts. its saddle cloth, howdah, and trappings were outlined with citrus fruits, peanuts, and corn. There was an obelisk of oranges, and even a towering medieval knight fashioned mostly out of prunes. (21) Behind the whimsy, however, there was a serious message. These fantastic exhibits told the visitors that California could produce anything, even during winter months, in unlimited abundance.

THE WALNUT ELEPHANT

It is tempting to guess why the food growers' concession chose such exotic forms for their fruits and nuts. Why not a California Grizzly or a Statue of Liberty? Whatever the reason, they were in keeping with the exotic themes of the fair. An obelisk of oranges might remind the visitor of the Egyptian Hall or the Fine Arts Building; the walnut elephant might call up visions of India expressed architecturally in the Mechanical Arts Building; the prune knight perhaps recalled the turrets and crenellations of the Administration Building or the Manufactures and Liberal Arts Building. Or the forms might suggest the place of origin of the product: oranges from the Near East, walnuts from Afghanistan and the northwest Himalayas, etc. But one can only speculate. The organic sculptures may well have been the products of simple whim on the part of the creators. The tradition of displaying agricultural abundance in sculptural form, borrowed from earlier American expositions, would be continued after 1894 by other states in exhibitions and fairs. Forts made of apples or canoes of butter were common. South Dakota's Corn Palace, redecorated with new ears of corn each summer, continues that tradition.