Exposition Nationale des produits de l’industrie agricole et manufacturière

Paris: 1849

by

Arthur Chandler

1849 exposition building

The final national industrial exposition in Paris was preceded by momentous changes. Louis Philippe, the last French monarch, had been deposed in February of 1848. Later that year, Louis Napoleon Bonaparte was elected president of the new republic. It would be his destiny to oversee the last of the French national industrial expositions and the first of the universal expositions.

The half-decade between the 1844 and the 1849 exposition saw the rise of numerous imitators throughout Europe. Berne and Madrid launched their own version of the Parisian event in 1845. Brussels, which had staged comparable expositions several times before, staged an elaborate industrial show in 1847. Bordeaux, tired of seeing all the glory go to the capital, attempted to host a modest industrial exposition the same year. In 1848, Russia staged her first industrial exposition at St. Petersburg, and Portugal her first at Lisbon in 1849. And, perhaps the most far-reaching in its consequences, Great Britain decided in 1849 that she, too, should host an industrial exposition – one that would outdo her French neighbors by inviting the entire world to exhibit in London.

For Louis Napoleon Bonaparte, the national exposition offered a number of exceptional political advantages. France was still in a turmoil, and needed some kind of unifying event to consolidate feelings of legitimacy around the Second Republic. There was the further problem of the expanding colonial empire. Algeria in particular, had been a thorn in the side of France for decades. Now that the North African nation seemed to be on the verge of submission, a national industrial exposition could be just the proper ritualistic event to announce the incorporation of Algiers into France.

It is not certain who made the initial suggestion that the 1849 event should feature agriculture on an equal par with industry. Perhaps this move, too, was partially a political decision calculated to heal the growing divisions between rural and urban France. Doubtless there was an underlying sincerity behind the exposition commission’s avowals that agriculture and industry were the twin pillars on which La France had built her prosperity. It would have been easy enough, of course, to feature agricultural implements as adjuncts to, or special cases of, industrial development. But the commissioners went all the way in including not only agricultural machinery, but the very raw material of rural life itself. It was a novel experience for the regular attendants of the Parisian expositions, as they surveyed the latest improvements in locomotives, pianos, and corset stays, to see and hear the grunting pigs and the cackling chickens.

President Bonaparte may have consciously devised an exposition that was sufficiently different from its predecessors to give the event his own unique stamp. But, at this stage of his career, he was shrewd enough to incorporate all the trappings of ritual and high drama of the past events. The opening ceremonies were copied in toto from those of the preceding expositions. Following then practice of Louis Philippe, Louis Napoleon chose Mondays to visit the individual exhibits. Only in the closing ceremonies would the President of the Second Republic attempt to outshine his predecessors in splendor.

The exposition commission was fully aware that, by opening up the exhibitions to farmers as well as industrialists, the event would probably be the largest in the history of France. And so it was. In spite of new restrictions on the kinds of exhibits that would be allowed, some 4,494 hopefuls were successful in obtaining permission to show their wares at the 1849 exposition. For the first time, the government made arrangements to defray all moving expenses of the exhibitors.(1) However, exhibitors were warned that the government would provide no insurance for any goods on display.

In an attempt to draw the largest crowd possible to the 1849 exposition, there was no entrance fee for visitors, except for a modest one franc charge on Thursday – and even these funds were donated to charity. The government was determined to fulfill the educational goal of the exposition by making sure that the only requirement for admission to the exhibit building was a sense of curiosity.

For the two month duration of the exposition, all exhibits were to be housed in an immense exhibit hall constructed on the Champs-Elysées – the same location that was used for the 1844 event. It soon be came evident, however, that even the 22,000 square meter interior was inadequate to house all the proposed displays. As a consequence, some of the larger machines were placed outside in separate structures.

One much-admired feature of the building was its provision for protection against fire. A drainage system was devised that caught the rain and channeled it into a large reservoir to which fire hoses were connected. Every day, seventy five guards and firemen were on duty. These men doubled as a security force and a fire department for the entire duration of the exposition.

The care given to the exterior ornament and interior comfort of the exposition building received praise from some, criticism from others. The basic rectangular shape of the building was brightened along the front entranceway by a long, classically-inspired facade. Pillars and pilasters broke up the horizontal expanse of the building’s front. A Greek pediment, filled with a scene in relief, surmounted the main entrance.

1849 exposition building facade

But critics were quick to point out that the so-called bronze relief in the pediment was merely plaster painted to look like bronze. The pilasters, inside and out, were painted to resemble the grain of chestnut wood. One British visitor, Matthew Digby Wyatt, decried both the expense and the deception of "these unnecessary and wasteful professional forgeries." He elaborated upon the point for his English readers:

Both internally and externally there is a good deal of tasteless and unprofitable ornament... If each simple material had been allowed to tell its own tale, and the lines of the construction so arranged as to conduce to a sentiment of grandeur, the qualities of "power" and "truth," which its enormous extent must have necessarily ensured, could have scarcely fail to excite admiration, and that at a very considerable saving of expense. (2)

Wyatt was sounding a theme which would have major repercussions in the subsequent construction of international expositions. The Crystal Palace of 1851 seems to have been built with Wyatt’s observations directly before the commissioners of that event. However, the Paris exposition universelle of 1855 would continue the trend set by the 1849 building: the use of classical ornament to hide, or to give dignity to, a utilitarian structure built of iron, glass, and plaster.

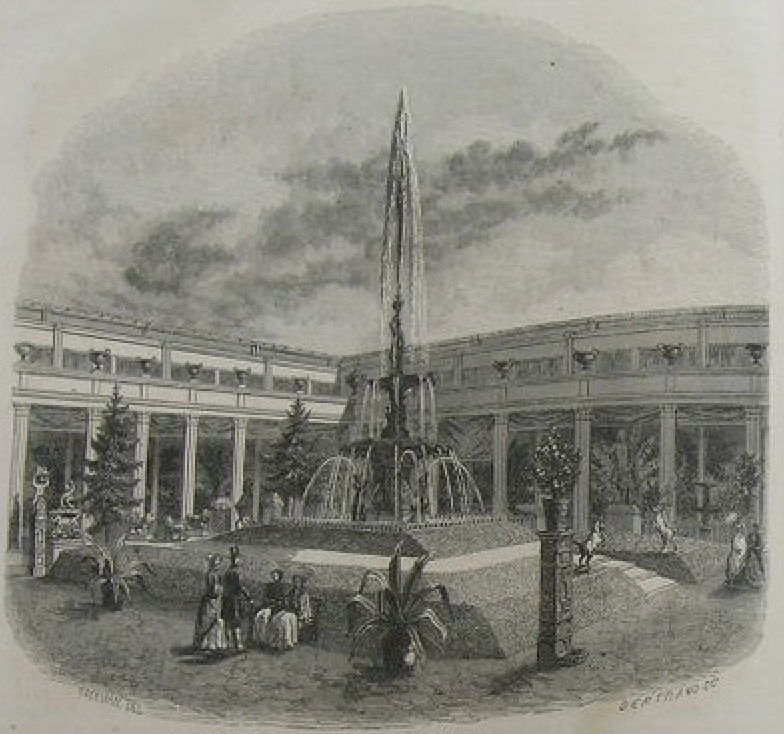

Though the exterior presence of the building may have given some offense, there were no critics of the interior courtyard. Placed in the very center of the building, this large, peaceful area provided for the relief of visitors who had spent hours in intense and lengthy observations of the exhibits. In the middle of the open-air courtyard was a large fountain. Scattered about were chairs, bronze and terra-cotta figures, and tasteful displays of flowers. Orange and lemon trees had been brought in for their fragrance. The whole ambience seems to have been one of relaxation and beauty. The 1867 univeral expositionwould repeat this idea of an interior courtyard at the center of the main exhibition hall.

Courtyard of the 1849 exposition

The exposition commission labored mightily to give the exhibits some sense of order; but, as always, the resulting system, when translated into the actual placement of objects within the building, gave viewers little or no idea of the guiding principles of selection. The 1849 exposition featured a ten-part classification system for its exhibits:

Agriculture and Horticulture

Algeria

Machines

Metal

Instruments of Precision

Chemical Arts

Ceramic Arts

Fabrics

Fine Arts

Diverse Arts

There are two new elements to this scheme of classification. One is the addition of agriculture and horticulture; the other is "Algeria" as a special section. Taken together, these two additions represent an attempt, on the part of the commissioners, to include as much of French enterprise as possible under the heading of the term exposition. It may seem startling, and perhaps even inconsistent, to view an entire nation -- Algeria -- as a product, generically categorized alongside of precision instruments and fabrics. But, at mid-century,this way of seeing colonial acquisitions presented no contradictions to the French mind.

By 1849, the French seemed to be in secure possession of Algeria. The long resistance to French force had collapsed in 1847 with the surrender of Abd-el-Kader. Under the Second Republic, France began the process of assimilating the country, partly with an eye to appropriating and augmenting its resources, and partly with a view to eliminating pauperism in France by sending poor people to colonize the new territory. The agenda of the Algerian commission at the 1849 exposition seems to have reflected these policies. The Algerian section was subdivided into the following sections, each with one or more commission members responsible for its direction:

Culture

Chemical products, oils, soaps, etc.

Raw silk

Tobacco

Minerals

Marbles

Fabrics

Wool oil

Cotton and Wool

Flour milling and couscous

Diverse industries

From this list, it is apparent that Algeria was regarded primarily as a source of raw materials for consumption by France. In his final address at the closing ceremonies, the minister of agriculture and commerce notes that the products exhibited by Algeria might seem modest; but what promise for future development! He assures his audience that, though Algerian products were judged by the same standards as those from the mother country, the judges may have shown some slight favoritism in awarding prizes to Algerian products, because "it is the hand of the conqueror that ought to open and extend itself for the good of the conquered people."(3) He goes on to say that the bargain struck with the Algerians is a fair one. In return for their raw products and native handiwork, French engineers have helped the Algerians constructs wells, irrigation systems, and dams that had already increased agricultural output enormously. At one point, the minister even draws on history to emphasize his point about cultural reciprocity:

The Arabs of the Middle Ages gave us their simple system of numbering and their admirable decimal system. We return the gift, so productive for the common good, by giving them our decimal metric system.(4)

The Algerian section and the agricultural exhibits were the new genuinely new features of the 1849 exposition. In all other departments, the French had little to show that could be seen as qualitative improvements over the 1844 event. In one respect, the 1849 exposition reverted to a practice of the earliest fairs by allowing eccentric exhibitors to display their strange inventions. Though the jury explicitly stated that only serious and widely applicable inventions would be allowed to enter, visitors were treated to stuffed hummingbirds that hopped from one branch to another by means of an ingenious mechanical contrivance. There was also a landscape created entirely out of human hair, ranging from platinum blonde to raven black. These bizarreries received no prizes; but it is pleasant to think that even in the midst of high idealism and lofty social agendas, there was still room in the odd corner for eccentric creators and their highly personal handicrafts.

In November of 1849, Napoleon III may or may not already have been plotting his transformation of the Second Republic into the Second Empire. But it is certain that the ceremonies attending the close of the 1849 exposition far surpassed, in size, grandeur, and sheer duration anything that had preceded it. The directors of the 1798 exposition had tried to replace religious ceremony by substituting a secular equivalent. President Charles Louis Napoleon Bonaparte brought in the full majesty of the church to enhance the effect of the final ceremonies. He employed artists, artisans, musicians, speech writers – a truly universal array of talent to dignify the final event with all the majesty the state could bring to bear.

The final ceremonies of the last exposition nationale serve the historian as a link between the first exposition of 1798 and the first universal exposition of 1855. In all three cases, the fanfare surrounding the presentation of awards served to proclaim, in ringing tones, that the rules of France and the new "nobility of industry" were destined to carry the nation to greatness. Louis Napoleon Bonaparte was particularly aware of the ritual significance of these events, and spared no expense to make them as impressive as possible.

On November 11, 1849, the ceremonies began at 9:45 in the morning. The presidential cortège assembled on the Champs-Elysées, then traveled slowly, surrounded by phalanxes of cavalry and lancers, to the Palais de Justice. As the President and his party entered the halls of justice, they were met and escorted by the members of the central jury of the exposition.

At the initial ceremony, President Bonaparte distributed the Legion of Honor awards, effusively praising their recipients. The entourage then exited the Palace of Justice and entered Saint Chapelle. The archbishop of Paris greeted the party, and delivered a eulogy in praise of the exposition and the new regime. The temporary arrangements inside Saint Chapelle were carefully planned to associate the authority of religion with the new prestige of the exposition. Throughout the chapel were prize-winning objects from the exposition itself. But the clearest symbolic linkage was the placement of two large, ornate trophies – one representing industry, the other, agriculture – at the foot of the altar.

In the half-century since the first exposition, we can trace the progress of the government’s attempt to invest the new faith in Progress with the authority of traditional religious practices. The 1798 event attempted to replace religion by placing the prize-winning exhibits in a "Temple of Industry" at the center of the exposition grounds. Now, 51 years later, and with the Catholic Church fully reinstated, the government adopts the majesty and authority of religion to hallow the efforts of industry. This alliance, to which the Church readily acceded, lasted until 1878, when the authorities of that year explicitly excluded religious ceremonies from the exposition events.5

After celebrating mass, the company returned to the main hall, where the decorations were "splendid, and appropriate to the solemn character of the occasion."(6) Across the central vault were nine large octagonal panels, each inscribed with the names and contributions of the most influential inventors in Western culture. It is fascinating to see which names the jury chose for this honor:

1450: GUTENBERG invents printing

1649: PASCAL invents the hydraulic press

1690: DENIS PAPIN invents the steam engine

1785: BERTHOLLET invents chloride bleach

1786: PHILIPPE LEBON invents gas lighting

1790: LEBLANC invents artificial soda

1800: ACHARD invents beetroot sugar

1810: DE GIRARD invents the mechanical spinning of flax

1822: FRESNEL invents lighthouse lenses

Aside from the fact that not all historians would agree as to the dates or originators of the above-named inventions, it is easy to note the overwhelming predominance of French names on the list. Were it not for the name of Gutenberg, we might assume that the exposition committee had chosen to single out only French inventions. But no: these are the leading inventions of all Europe; and France is the leading force in the making of these inventions. It is as though Great Britain and Germany had no hand at all – or, at best, had only a supporting and secondary role – in the making of the Industrial Revolution

Along the cornice of the main ceiling ran 18 names of the main divisions of human invention and production: medicine, geography, astronomy, painting, architecture, sculpture, furniture, ceramics, agronomy, horticulture, metallurgy, mechanics, goldsmithing, watch-making, photography, glass-making, and stringed instrument-making. This list presents a number of interesting insights, and not a few puzzles. Most obviously, it presents a concise list of what the French viewed as the apex of human achivement.

But questions arise immediately. Why "stringed-instrument making," and not music generally? After all, painting and architecture had their own categories apart from any specific chemical or engineering techniques that formed part of their craft. And why stringed instruments alone, and not woodwinds or pianos? Pianos, especially, had come to dominate the musical instrument section of the last several national expositions. But the stringed instruments, and the violin in particular, were regarded as the aristocrats of musical instruments. Therefore, they received a place of honor, while the lesser nobility of woodwinds, brass, and keyboards were excluded.

Painting, architecture, and sculpture – the traditional core of the fine arts France – were represented, in spite of the fact that no artists ever exhibited their works at the industrial expositions (bronze sculpture were exhibited only as specimens of the foundryman’s skill). In this and several of the previous expositions there had been fine arts sections; but these were confined to engraving, woodcuts, and other minor arts.

Photography, though, finds itself among the honored. Though scarcely a decade old, this new visual medium was recognized at once to have an unlimited potential. And, though photography had already moved far beyond the original processes of the daguerreotype, the source invention was unarguably French.

Banners bearing the inscription "honor to labor" were draped from every pilaster in the room. There were numerous obeisances to science, industry, and technology, of course. But this specific acknowledgement of the worker was something new, and would later form a part of Emperor Napoleon’s social philosophy undergirding both the 1855 and 1867 universal expositions.

But the concept of "worker" was not quite the Marxist idea of the urban proletariat. When the committee planned its ornamented frieze that encircled the entire room, they made explicit just who these workers were: "modest workers who supplemented scientific instruction with the spirit of observation and their natural genius"(7) – in contrast to the savants who had devised theories and techniques by means of study alone. Thus Jacquart and Montgolfier, workers who carried out their ideas by building, testing, and observing, were listed along with Pascal and Monge, savants of the "noble sort" who achieved their ends by thought alone.

The minister of agriculture and commerce gave a long, thoughtful, and very detailed description of each of the ten sections of the exposition, and concluded: "In the name of the grand jury of national industry, by our soul and conscience, before God and man, we declare with a single voice that our maligned and threatened industry, had not only served well our country, but the entire human race.(8)

After lengthy applause following the expression of these sentiments, President Bonaparte took the podium. He asserted – and would in later years repeat the assertions – that "the degree of civilization of a country is manifested by its progress in industry and art."(9) He urged the people of France to continue to do their duties, and promised to do his part.

The ceremony concluded with a roll call of all 3,738 winners of awards.

*****

The 1849 exposition in Paris drew more assessments than any of its ten predecessors. There were not one, but four official reports on the event. The department of the north issued a separate report specifically for the use of industrialists in that area.(10) There were two official German reports and one English. Perhaps most influential of all were the reports in the prestigious English periodical, The Art Union. In a thorough, two-part coverage of the event, the English journal did more than point out what the writers perceived as the successes and failures of the French event. In the first installment, which appeared in August, 1849, The Art Union clamored for the British to match and beat the French efforts. After surveying the highlights of the 1849 exposition, The Art Union notes:

We are happy to say that with scarcely an exception, all the manufacturers of highest standing have contributed largely to the Exposition; we believe such would be the case in England if an exhibition of similar nature and extent could be formed... We trust that the subject will not be overlooked by those who are best able to forward the project, seeing, as they must, its vast advantages in producing a healthy emulation.(11)

Then the writer or writers continue their argument in an extended footnote to this plea:

About three years ago we informed our readers that we had been in correspondence with some of the leading members of the government with a view to the experiment in England of an Exposition similar to that we have recently witnessed in France. Their opinion was that the time had not yet arrived; that English prejudice against publicity had not yet been overcome; that the public on the one hand and the manufacturer on the other were not prepared for an exhibition as we contemplated. We could not combat this opinion, and we relinquished the attempt; asking leave, however, to bring the subject again under the notice of the authorities, and expressing strong belief that the object was fully capable of attainment, and with the most beneficial results. We find wit very cordial satisfaction, that the Secretary and Council of the Society of Arts have taken the matter in hand; and we trust they will succeed in bringing it to a successful issue.(12)

The Art Union then goes on to make some specific suggestions about the organization of the event, and recommends Hyde Park as the logical choice for the exposition grounds.

By the time of the next installment, the matter had been decided. The Art Union notes that they have already given coverage to the French exposition of 1849. Now, however, events in England dictate that their coverage take a somewhat different perspective. The writer, in one enormous sentence, sums up the matter thus:

But in consideration of the fact that the idea of bringing together the best selections of every species of products will, in the year 1851, be carried out in this country on a more extended scale than it has yet been elsewhere (the Exposition, on that occasion, instead of being National being European, whereby the English manufacturer will be enabled to compare and weigh his own with foreign productions, to improve by the lessons thus taught his efforts in project and in execution, and to open fresh channels for British Commerce and British Art), we have deemed it necessary to add an appendix to our former remarks, that the public may be made aware, from Continental experience, of the best means for realising so desirable an end, and may be put in possession of the history of those failures which it will be necessary to avoid.(13)

***

Here, then, it the bridge between the eleven French national exposition and the future international exhibitions that continue to be held today. There is still the nationalistic note, though in The Art Union it has been toned down to "healthy emulation"; still the desire to improve local invention; and still the desire to incorporate art along with industry as a total presentation of the nation’s achievements. Thenceforeward, the world itself will come to the stage of the international exposition.

Exposition medal designed by Antoine Bovy

The date on the front denotes the founding of the Second Republic

NOTES

1 Entries from the departément of the Seine were exempted from this reimbusement, since the exhibitors from Paris were judged to be close enough to the exhibit space to bear the transportation and installations costs themselves.

2 Quoted in The Art Union, August, 1849, page 371.

3 Rapport du jury centrale sur les produits de l’agriculture et de l’industrie exposés en 1849 (Paris, 1850), page LXII.

4 ibid., page LXIV.

5 For a description of the exclusion of religious services at the 1878 exposition, see page XXX below.

6 Rapport, page XXIX.

7 Rapport, page XXXI.

8 Rapport, page LXIX.

9 ibid.

10 Kuhlmann, C.F. Exposition nationale des produits de l’industrie agricole et manufacturière de 1849. Rapport de jury dépertemental du Nord: analyse de la situation industrielle du département (Lille, 1849).

11 The Art Union, August, 1849, page 234.

12 ibid.

13 ibid., page 371.

STATISTICS

Opening Date: May 1

Closing Date: November 11 (Distribution of Awards)

Site: Champs Elysées

Exhibitors: 4542

Top Official: L. Buffet

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Art Union, August, 1849

Bères, E. Compte-rendu de l’exposition industrielle et agricole de la France en 1849. (Paris, 1849)

Exposition nationale des produits de l’industrie agricole et manufacturière, 1849. Catologue officiel. (Paris, 1849)

Kuhlmann, C.F. Exposition nationale des produits de l’industrie agricole et manufacturière de 1849. Rapport de jury dépertemental du Nord: analyse de la situation industrielle du département (Lille, 1849)

Livret de l’exposition nationale des produits de l’agriculture et de l’industrie, 1849. (Paris, 1849)

Rapport du jury centrale sur les produits de l’agriculture et de l’industrie exposés en 1849 (Paris, 1850, 3 volumes)