THE EXPOSITION COLONIALE INTERNATIONALE DE PARIS, 1931

by

Arthur Chandler

Expanded and revised from World's Fair magazine, Volume VIII, Number 4, 1988 and Contemporary French Civilization, Winter/Spring, 1990

The Family of France

The first French empire died on the field of Waterloo in 1815. The Prussian troops and Parisian rebels ended the Second Empire in 1871. But through these and other violent fluctuations in French political life, the real French Empire – the empire of her colonial possessions around the world – grew steadily throughout the nineteenth century. After the first World War, France found herself in command of the most extensive colonial empire in the world: some 47 nations whose official language was French and whose governments were under some degree of obligation to France. To bring these peoples together in the capital city in order to educate the French nation as to the importance of their colonies – this was the primary goal of the Exposition Coloniale et Internationale de Paris.

The unspoken philosophy of the exposition, however, was the same mission civilisatrice that had guided and justified French foreign policy for more than a century. "To colonize does not mean merely to construct wharves, factories, and railroads," wrote Le Maréchal Hubert Lyautey, Commissioner General of the exposition. "It means also to instill a humane gentleness in the wild hearts of the savannah or the desert."[1] One of the goals of the exposition, therefore, was to demonstrate that the French colonial effort was achieving those goals, and that colonial industry, however primitive when compared to the achievements of the "civilized" world, was showing promising signs of advancement from savagery to civilization.

But if the exposition coloniale were to be more than an elaborate display of French policy, it had to be shown that other civilized nations had the same goals, and that the will of the West to continue its civilizing mission was still strong. Pierre Deloncle, writing for l’Illustration, provided the proper rhetoric for proclaiming the colonial effort to be a common destiny for Western civilization as a whole:

At a time when certain intellectuals and political parties are freely talking of a failure or a "decline of the west," the colonial exposition at Vincennes comes at a ripe moment to affirm that the great European nations (and the United States with them) are not in the least disposed to acknowledge this failure or to renounce the civilizing mission that have undertaken.[2]

In this light, the exposition coloniale takes on the air of an elaborate justification: a proof, to herself and to other colonizing powers, that the task of bringing civilization to the uncivilized is a task undertaken by Europe and America. Attacked from the left for their paternalistic and exploitative attitudes, and by the right for a failure of nerve, French supporters of the colonial enterprise looked upon the exposition as an opportunity to furnish proof to the world that colonialism was accomplishing its noble goals.

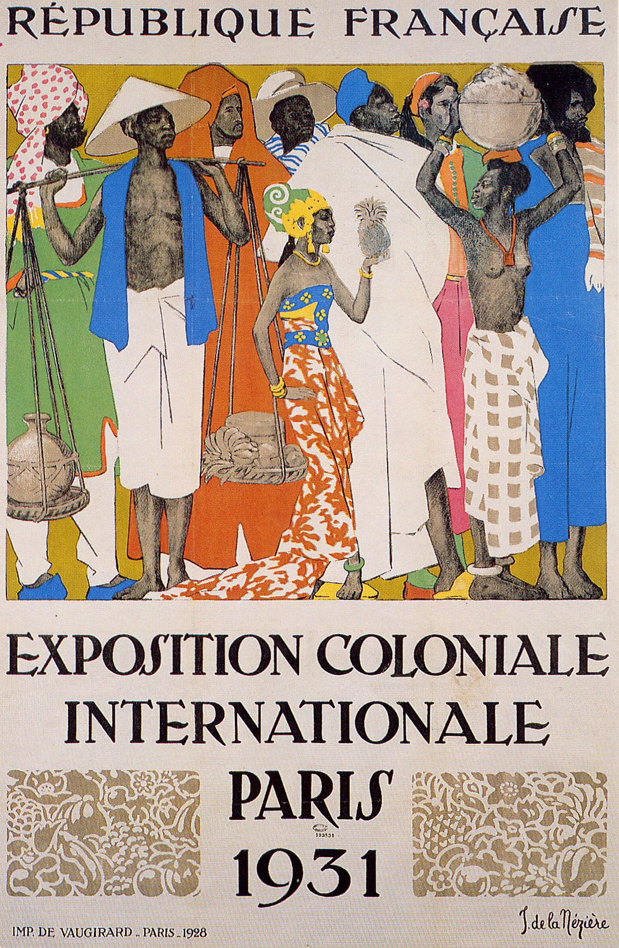

Two Posters Depicting the Mission Civilisatrice, 1931

(Click the image for a lightbox view)

Note that the woman in the right poster wears the traditional spiked crown — a legacy from the 1855 Exposition Universelle — and grasps a sheild bearing the traditional motif ideas of all the French expositions: Progress, Civilization, and Commerce.

A Quarter Century of Planning

The 1931 colonial exposition was the culmination of 25 years of planning and thought. A National Committee for Colonial Expositions had been formed in 1906, with the express purpose of advancing the belief that France was now both an empire and a republic – and empire with respect to her protectorate, a republic at home. In 1912, Minister of Colonies Albert Lebrun urged that Paris should host a colonial exposition, and that the spike of the fair should be the creation of a permanent museum devoted to the art and society of the colonies. Accordingly, on June 23, 1913, a decree was signed affirming these principles, and designating Paris as the host city, since "Paris is without question the capital of such great expositions. In the capital, the brilliance of these fairs covers all of France, and indeed illuminates the universe." [3] A tentative date of 1916 was set for the colonial exposition.

There soon arose the almost inevitable opposition from the provinces, with the city of Marseille leading the way. Such objections to the hegemony of Paris had long been part of the controversy in France surrounding world's fairs. But this time, the provinces were not to be swept aside so easily. Marseille was the second largest city in France, and possessed considerable economic resources and political power to combat Paris.

In addition to the usual argument – that the honor and profit resulting from expositions always went to the "head" of France rather than to her "body," the provinces – loyal citizens of Marseille questioned whether Paris was in other respects the appropriate place to stage a colonial exposition. After all, the skies there are too often gray and rainy. The weather of Marseille is much closer to the climate of the tropical colonies, the Marseille supporters argued. In addition, Marseille was, by its seagoing nature, more adventuresome than Paris, which, according to Charles Roux, was made up of mere "explorers of the shrubbery along the boulevards." [4]

The events of the First World war overwhelmed this controversy for the time being. But in 1920, the battle between Paris and Marseille was joined again. In defiance of the capital, Marseille opened its own national colonial exposition in 1922. Though it was restricted to exhibits featuring French colonies, many of the buildings that would arise in Paris in 1931 were first anticipated by the Marseille exposition – notably the thatched African village huts and the temple of Angor Wat.

The Indochina Palace at the Marseille Exposition, 1922

Paris could afford to cede precedence to Marseille. While plans and negotiations for the Parisian colonial exposition were under discussion, Paris hosted the Art Deco fair of 1925. Though not directly related to the colonial exposition that would come six years later, the art deco fair had one major impact on the later event. Parisians were not willing for the heart of their city to be desecrated for six years with the noise and dust emanating from the building and demolition of two large expositions. As a consequence, the colonial exposition planners turned their thought to other suitable locations for their event.

After a good deal of debate, it was finally decided that the colonial exposition should take place in Vincennes, the site of an old royal castle and, since the days of Napoleon III, a lovely public park. Bonds were sold, and a guaranty company formed to secure the necessary financing for the venture. To head up the entire affair, the government appointed Le Maréchal Lyautey, a distinguished and experienced military man. Lyautey had been in charge of the Franco-Morrocan colonial exposition held in Casablanca in 1915, and held definite ideas about how such an affair should be organized.[5] Though appointed chief commissioner of the exposition coloniale in 1927, he resisted all attempts to hurry preparations, insisting that 1931 was the earliest date by which the event could be launched successfully. Once the date was set, however, Le Maréchal insisted that all exhibits had to be completely finished fifteen days before the May 6 opening date. Any exhibitors failing to meet this requirement would find their unfinished exhibits torn down and hauled away – at their expense!

Plan of the 1931 Exposition (Click here for more images)

All work was finished on time.

Colonial Enterprises

The buildings and grounds of the event covered some 500 acres of land – making it the most extensive exposition in French history. The fair surrounded the Daumesnil Lake, with its two islands, and included a substantial zoological garden. Broad avenues and ample distance between buildings gave the exposition a spaciousness unknown in previous world’s fairs in the capital city. For the first, and perhaps the only time in the history of Parisian expositions, there were no complaints about a shortage of exhibit space.

All countries had more than enough room for their displays; but the list of exhibiting countries is a curious one. Some nations, for a variety of reasons, chose not to erect national pavilions. England, who harbored similar feelings about her own empire on which the sun never set, could see little profit in bringing her subject peoples to Paris. Germany had been stripped of her colonial possessions as a result of her defeat in the First World War, and felt the urge to come to Paris simply to gaze on former possessions that were now "Sous Mandat" protectorates of France. Many countries, including England and Germany, contented themselves with informational displays in the City of Information building next to the main Entranceway of Honor.

The host country of an exposition typically took a plurality of the exhibition acreage, and naturally outshone her rivals by the sheer quantity of her exhibits. But the colonial exposition of 1931 carried this tendency to its conclusion. France completely dominated the colonial exhibits, as she meant to. The exposition was conceived primarily as an attempt at fostering a communal feeling of solidarity among her colonies. Indigenous peoples from French colonies around the globe would come to Paris and feel a surge of pride in belonging to such a glorious enterprise – such was the hope.

Those nations that did erect pavilions did so with a variety of motives. Italy, which had little to show in the way of grand colonial enterprises, proudly displayed the history of her colonizing in the days of the Roman Empire. The Italian pavilion itself was a reconstruction of the basilica of Septimus Severus, erected in Libya during the era of Imperial conquest. Commissioner general Lyautey himself commented on the "union of force and beauty" of the Italian pavilion. The new Italian colonial ventures in Tripoli and Somalia were thus given historical perspective and, in the eyes of the exhibitors, justification.

The Italian Pavilion; Armando Brasini, architect

Other exhibiting European nations proudly set forth, in pavilions built along the lines of native architecture, the efforts of the mother countries to improve the life of the indigenous peoples in their colonies. Displays of schoolhouses, medical equipment, and improved transportation all pointed to the good done by Holland, Belgium, Portugal, and other European powers in the lands they had chosen to occupy. Close by these exhibits were others that told the story of why the European powers were there in the first place: raw materials. Displays of coffee, rubber, precious metals and exotic foodstuffs were accompanied by impressive statistics showing how valuable colonial products were for their master countries.

Only one pavilion seemed to show unqualified altruism. Denmark's building at the exposition featured her efforts to colonize Greenland. Dioramas showed "Esquimeaux" and their dog trains surrounded by the bleak landscape and bitter cold of the largest island in the world. No shipments of gold or cinnamon, pepper or petroleum: only an unremitting battle against the elements, with the Danish government contributing its scientific expertise to make life in Greenland more tolerable.

The Denmark Pavilion

The United States was the only non-European country exhibiting as a colonial power. The American building at the exposition was a close replica of George Washington's house at Mount Vernon, complete with the bedroom set aside for Lafayette – a gesture that pleased the French hosts enormously. The inherent irony of the American exhibit – that it was housed in a building of the man who led the fight against colonial tyranny in the United States – was evidently completely lost on both the French and the Americans. Flanking the Mount Vernon building, but constructed in a style that blended harmoniously with the main structure, were a series of cottages featuring displays of America's burgeoning colonial empire: Alaska, Hawaii, Puerto Rico, the Virgin Islands, and Samoa – all of which were presenting themselves for the first time at a Parisian exposition.

Mount Vernon Reconstruction at the 1931 Exposition, by Sears and Roebuck (click here for the story of its construction)

But the American and other, non-French pavilions were mere side shows compared to the splendor of the exhibits of the French colonies. A circular train, mounted on a narrow-gauge railway, would carry visitors around the Lac Dausmenil, stopping at the foreign pavilions, and finally depositing voyagers at the head of the Grande Avenue des Colonies Françaises. On this grand avenue, and on several of the radiating streets, stood the splendid and exotic structures representing the indigenous architecture of the French colonials in Africa, the Near East, the Fair East, and Oceania.

North African nations had long been present at Parisian expositions; and visitors who had attended earlier fairs could recognize the familiar perfumes, carpets, ornamented brass and hand-tooled leather, the exotic food served by colonials who spoke French with native accents.[6] Still, the experience of dining at exotic eateries was new and strange to many visitors. One woman, having ordered "pilaf" in a Maroccan restaurant, sat waiting in anticipation of some bubbling concoction of native plants and the flesh of wild beasts. When the dish was served, she could only berate the waiter, in tones of disappointed outrage, "Why, this is only rice!" Two observers, Jean Camp and André Corbier, complained in their account that many such restaurants "offer us dishes with barbarous names which only attempt to disguise vegetable soup, stewed chicken, and little peas à la Française." [7]

But to most Parisians, the Arabic colonies were familiar stuff. Far more interesting were the West Indian and African nations, some of which had been acquired only since the time of the First World War. French audiences had been primed to appreciate more of black culture since the triumphant conquest of Parisian entertainment by American jazz musicians and the talents of Josephine Baker. She had captured the imagination of the Parisian chic monde, and many of the lily whitest of women were now sporting tans as signs of their own inner tropic nature. In the pavilions of Guadeloupe and Martinique, one could attend a festival where brightly-garbed performers mixed French, African, and Indian moods in their dances, while onlookers could enjoy the tangible pleasures of native rum or cocoa. To "go native" became the current fashion among trend-conscious Parisians and international fellow-travellers.

The Martinique Pavilion at the Exposition coloniale

The Orchestre Stellion of Martinique at the Exposition

The African pavilions were huge structures of wood covered over with bulky thatching – and designed by French architects. Inside, dioramas told of the history of French civilizing influences in each country, and of the native handiworks. Graphs showed the decline in mortal illnesses and an improvement in physical health throughout the French protectorates. To preserve the authenticity of feeling at these pavilions, an exposition regulation stipulated that no Africans, or any other colonials, could wear European clothing on the fairgrounds.

Togo and Cameroon pavilions; Louis-Hippolyte Boileau, architect

The Madagascar display saw two distinct variations on the otherwise unvarying African displays of French pride and native artisanship. For one event, two authors, Pierre Camo and Roger Chardon, conceived of the idea of tapping into the great African oral tradition by creating an epic hymn to colonial enterprise. A Madagascar actor was hired to memorize the text; and he then appeared at one of the evening fetes to recite such ecstatic tropes as : "Every year our factories send forth six thousand tons-worth of cooking pots to France." Perhaps the authors hoped that this prose and prosaic epic would work its way into native oral culture, and instill the natives with a sense of ritual awe at their own contributions to the mother country.

Meanwhile, outside the exhibit building, an odd skit was taking place. A Madagascar woman rounded up one of her little boys, stood him up in a tub and proceeded to wash him down with clear water. As the scrubbing advanced, the child glistened with cleanliness, but the water turned progressively dirtier. Finally, the woman reached down, scooped up a bottleful of the liquid, and had the boy drink it down. According to Jean Camp and André Corbier, visitors came away persuaded that this was how the black race maintained its shadowy color.

The most imposing structure on the Avenue of French Colonies — indeed, the most impressive of all structures at the exposition — was the Temple of Angor Wat, a faithful rendition of the original Cambodian structure by the French architectural firm of Charles and Gabriel Blanche. Inside the temple, visitors encountered the dutiful array of statistics and displays of agricultural production, as well as a panoramic account of the history of Indo-China. But it was the sheer size and grandeur of the building itself that drew people to the Angor Wat temple. Surely here, visitors might think, is a symbol of grandeur from another culture – proof that they, too, had architectural traditions as lofty as any in Europe.

Night View of the Angor Wat Pavilion; Charles and Gabriel Blanche, architects

(Click the image for a LIGHTBOX view)

But Angor Wat did not symbolize, for the exposition organizers, any such grandeur. In fact, according to Claude Farrere, "The temples of Angor symbolize not so much a unified and indivisible Indo-China – this is a puerile concept of Soviet politicians and their ignorant dupes – as a dead civilization killed by the worst sort of native violence, a civilization which France is attempting to revive today." [8]

The Angor Wat temple represented, for the supporters of French colonial policy, all that the mother country was attempting to do, in the face of public indifference and political hostility from the left. In humanitarian terms, French colonial policy makers felt genuinely that France could and should exert her powerful civilizing influence on the under-developed nations of the world. After all, was not Paris the major civilizing city in Western civilization? Could France do anything less than bring the best of Western methods of industrial production, medicine, and fair governance to nations previously suffering under the tyranny of bloodthirsty despots?

The urge to bring civilization to savage lands had not always been in the hands of governments, of course. For centuries, religious institutions had sent out missionaries to convert natives to Christianity and to halt practices which, in the views of their leaders, were abhorrent to God. The exposition coloniale featured an entire Pavilion of Missions, in which Protestant and Catholic missionary enterprises displayed their philosophies of assistance and conversion. France, which had consciously begun to exclude the Church from any official connection to the universal expositions in 1878, now welcomed both Protestant and Catholic missionaries back into the official governmental fold as an important and useful element of the Civilizing Mission.

Supporters of the missionary effort were aware that there efforts were not without opposition in France. Such opposition, however, was seen by the missionaries and their advocates simply as a desire to keep primitive peoples in a prolonged state of infancy. After all, wrote Jérome and Jean Tharaud, the European position with respect to her colonies is very similar to "our position in Europe when it became necessary to draw us out of the paganism of the Celts, Germans, and Slavs."[9] The religious element of colonization is thus transformed into a necessary and fitting component of the civilizing process.

Down with the Exposition!

There were dissenting voices, however, even in France. This mission civilisatrice, said the leading left-wing newspapers of Paris, L'Humanité and Le Populaire, was merely a cover for exploitative foreign conquest, calling the event "The Imperialist Fair of Vincennes." Even the Surrealist writers took to distributing tracts entitled "Do Not Visit The Exposition."[10] Aragon, one of the leading Surrealist writers, even organized a "counter exposition," housed in one of the pavilions left over from the Art deco fair of 1925. Drawing on the personal collections of his friends, Aragon brought together sculptures from Africa, Oceania, and the Americas, so that the people could see the artwork of these countries on their own terms, away from the atmosphere of imperialism that pervaded the "Permanent Museum of the Colonies" at Vincennes. As for Angor Wat itself, the socialist leader Léon Blum commented acidly: "Here we have rebuilt the marvelous stairway of the temple of Angor Wat, and we watch enthralled the sacred dancers; but, in Indo-China, we are shooting, we are deporting, we are imprisoning these people."[11]

Anti-Exposition poster published by the Communist Party, 1931

(Click the image for a LIGHTBOX view)

At the center of the image, surrounded by implements of massacre and addiction, the Communist party uses the guilloitine as the centeral symbol, not of revolutionary freedom, but the French government’s policy of destroying colonial “workers and peasants.”

In spite of the attitude of French superiority that prevailed at the colonial exposition, one of its major goals was to demonstrate to the people that the colonies were not simply the homes of exotic peoples and strange customs: they were the source of vital resources contributing to the health of the French economy. The relationship of France toward her colonies, as argued in all the official documents for the exposition, was one of reciprocity: in exchange for the benefits of French civilization, the colonies would provide material goods to France.

With respect to the colonial presence in Paris, there is a decided difference in the major objective of this exposition and the previous five expositions universelles. From 1855 to 1900, colonial pavilions were set up with an eye toward impressing the natives. Representatives from Senegal, Tunisia, or Vietnam would come to the Queen City, experience the power and glory of La France at the exposition, and hopefully return home with a sense of pride in belonging to such a benevolent and puissant enterprise. But in 1931, the exposition organizers, backed by Minister of the Colonies Léon Perrier, were not primarily out to impress the natives: they were attempting to impress upon French people the importance of the colonies for the health of France, and the humanitarian good the empire was bringing to her subject nations. The inscription on the wall of the Museum of African and Oceanic Art makes clear the French sense of purpose behind the exposition. It reads: "To her sons who have extended the empire of her genius and made dear her name across the seas, France extends her gratitude."[12]

In many important respects, the Exposition Coloniale Internationale de Paris could be counted a success. The total number of visitors to the fair – 33,489,902 paid admissions, plus an estimated one million free tickets – made this the second largest attendance of any Parisian exposition. And, according to one tally of the final receipts, the colonial exposition made a substantial profit of some 33 million francs.

In addition to the cash profit, the exposition coloniale left behind two permanent legacies to the city of Paris. The section of the fairgrounds that housed the display of exotic animals became the basis for the zoo in the park of Vincennes. The art gallery for the exposition, designed by Jaussely and Laprade, with decorative stone murals by the Prix de Rome winner Alfred Janniot, became the "Permanent Museum of the Colonies" (today called the Museum of African and Oceanic Art). In 1931, this museum displayed not only the art from French colonies, but also works by renowned French artists, such as Cezanne and Gauguin, who at some point in their careers had drawn on non-Western art for inspiration and subject matter.

Details from the Alfred Janniot Murals: "Indochina" and "Madagascar"

(Click the image for a LIGHTBOX vew)

There still remains the question, however, of whether or not the exposition coloniale achieved its major goal: to educate the French people as to the importance of the colonies to France. For at least a century, the French nation, even and especially the intellectuals and artists, regarded the colonies as mysterious, far-away places where incomprehensible people practised their inscrutable ways. What attracted people to the Turkish baths of Ingres, the harem scenes of Gérôme, or the island village women of Gauguin was precisely their strangeness. And it was this same exotic allure that drew people to Vincennes in 1931. Thomas August, commenting on the decision of the commissioners to use this exoticism to attract people to the fair in order to educate them, asks rhetorically, "Will masses of people at any time line up to read statistics about groundnut production and new approaches to rubber cultivation?" [13]

Most people, it seems, came to the exposition coloniale to enjoy themselves. They came away satisfied, much in the same way that people come away from a meal in a foreign restaurant. People opposed to colonialism did not change their minds; people already in favor of the enterprise could feel that their convictions were further reinforced. The vast majority of visitors went about their business as before. Governmental colonial policy went unchanged.

The one exception is the effect of the exposition on a sizeable portion of the French youth who attended the event. The colonial office was concerned that France needed the talents of bright young men to administer the Empire. As a consequence, there was a concerted effort on the part of exposition officials to attract students of all ages to the fair. Pupils from primary and secondary schools, trade schools, and teacher training institutions participated in the "Tour the World in Four Days" program, which involved an intensive study of all the major exhibits at the exposition. In a later study of this effort, William Cohen remarked:

For the six months of its duration the exposition continued drawing visitors, especially school children. It inspired a large number of them to aim at overseas service. Many of the men who entered the colonial school in the 1930s mentions the Vincennes exposition as having had an important influence on the choice of a career.[14]

In the long run, of course, the effort was futile. France, like all other European countries, lost partial or complete control over her possessions. In some cases, such as Vietnam and Algeria, the struggle against French colonialism was especially tragic, and cost both sides tens of thousands of lives before the conflict was ended. And indeed, France without her Empire seems to have survived tolerably well without the forced importation of colonial products to bolster the quality of life. But as the 1930s progressed, other events were taking shape that would have far greater immediate effect on France than the loss of her empire. The great Depression, the bitterly divisive election in 1936, and the acting out of the ambitions of Hitler and Mussolini. By the time of the next and last great Parisian exposition in 1937, France would find herself on the brink of losing far more than her overseas empire.

NOTES

1 l’Illustration, November, 1931, n.p.

2 l’Illustration, May, 1931, n.p.

3 Cited in Philippe Bouin & Christian-Philippe Chanut, Histoire Française des Foires et des Expositions Universelles (Paris, 1980), p. 179. Note the similarity in tone with Victor Hugo's claim for the universality of France in 1867.

4 Ibid., page 180

5 Lyautey succinctly stated what he saw as the basic difference between the Moroccan expositon and the Paris event: "The exposition at Morocco gave to our colonials confidence in the designs of France and their proper role in those designs.... The exposition assured them that France was, in spite of enemy [German] propaganda, a nation sure of iteself and confident of victory." – l’Illustration, November, 1931, n.p.

6 So far had the North African nations advanced in their imitation of French ways that they were now launching their own expositions: in Egypt, the Exposition Française au Caire presented French culture in the colonial setting at Cairo; in Algeria, the Exposition générale du Centenaire de l'Algerie marked the 100th anniversary of the military occupation of Algeria by French troops (one wonders about the spirit into which the Algerians entered in celebrating the conquest of their own country).

7 Histoire Française, page 189

8 "L'Ankor et l'Indochine," in l'Illustration, May, 1931, n.p.

9 l’Illustration, May, 1931, n.p.

10 André Breton, Paul Eluard, Aragon, Maxime Alexandre, "Ne visitez pas l'Exposition Coloniale" (Paris, 1931)

11 "Moins de fêtes et de discours, plus d'intelligence humaine," in Le Populaire, May 7, 1931

12 The inscription is followed by a list of names of Frenchmen, from the Crusades down to the colonial wars of the twentieth century. It may be difficult for the reader today to grasp the frame of mind which, in 1931, saw the names of Crusaders and colonial governors as men who made the name of France beloved in distant lands.

13 l’Illustration, November, 1931, n.p.

14 "The Colonial Exposition in France: Education or Reinforcement?" in Proceedings of the Sixth and Seventh Annual Meetings of the French Colonial Society, 1980-81. Washington, D.C., page 153

15 Rulers of Empire: The French Colonial Service in Africa, Stanford, 1971, pp. 105-106

STATISTICAL APPENDIX

Opening Date: May 4, 1931

Closing Date: November 4, 1931

Size of Site: 500 acres

Official Paid Attendance:33,489,902

Exhibitors: 12,000 (including vendors)

Expenses (estimated): 285,181,652 francs

Receipts (estimated): 318,378,938 francs

Profit to Government (estimated): 33,197,286

Top Official: Maréchal Lyautey, Commissaire général de l'Exposition coloniale

BIBLIOGRAPHY

August, Thomas. "The Colonial Exposition in France: Education or Reinforcement?" in Proceedings of the Sixth and Seventh Annual Meetings of the French Colonial Society, 1980-81. (Washington, D.C., 1982).

Blum, Léon. "Moins de fetes et de discours, plus d'intelligence humaine," in Le Populaire, May 7, 1931.

Bouin Philippe, and Chanut, Christian-Philippe. Histoire Française des Foires et des Expositions Universelles (Paris, 1980).

Breton, André; Eluard, Paul; Aragon; and Alexandre, Maxime. Ne visitez pas l'Exposition Coloniale (Paris, 1931).

Cohen, William. Rulers of Empire: The French Colonial Service in Africa (Stanford, California, 1971).

Hodeir, Catherine. "L'épopée de la décolonisation à travers les expositions universelles du XXe siècle," in Le livre des expositions universelles, 1851-1989 (Paris, 1983).

– "Une journée à l'Exposition coloniale," in Histoire, Number 69, 1984.

Homo, Roger. "Lyautey et l'exposition coloniale internationale de 1931," in Comptes rendus mensuels des Séances de l'Academie des Sciences d'Outre-Mer (Paris, 1961).

L'Illustration, May, 1931.

Olivier, Gouverneur général. Exposition Coloniale internationale et des pays d'outre-mer. Rapport général présenté par le gouverneur général Olivier (Paris, 1933).

Pala, S. Documents exposition coloniale Paris 1931 (Paris, 1981).

Prat, Veronique. "Pour Une Fete Coloniale," Connaissance des Arts, No. 349, March, 1981.

Streel, Du Vivier de. Les Ensiegnements généraux de l’exposition coloniale (Paris, 1932)

Here is my account of the background for the Paris expositions