WHAT THE CROWDS saw at the California Midwinter International Exposition in 1894 was a Californian image of the world the international drama in which San Francisco was determined to win its rightful place. De Young, afraid that the San Francisco fair would suffer by comparison if it tried to imitate the carefully coordinated Greco-Roman architecture of the Columbian Exposition, forbade any references to the Classical tradition in the major Midwinter Exposition buildings. San Francisco architects, though, were more than equal to the challenge. They were used to turning out exotic Victorian fantasies for their local nouveau riche clients, and therefore felt quite at home spinning out the multicultural extravaganzas that adorned the Grand Court of Honor at the Midwinter Fair.

The major buildings at the Chicago exposition all drew on the established architectural vocabulary of Europe and the ancient world. At San Francisco, highly personalized syntheses of world architecture flanked the Court of Honor. In Chicago, the main buildings were all white, in deference to their designer's notion of classical purity. In San Francisco, the "Sunset City" drew its color scheme from the spectrum that suffuses the skies over the Pacific horizon at evening time.

Thirty-six California counties, five American states, the Arizona Territory, and thirty-eight nations were represented by a building or an exhibit at the fair. The products displayed in the fair's buildings were judged in five major categories: agriculture and horticulture, manufactures, liberal arts, ethnology and invention, and the fine arts. Of the 2,083 prizes awarded, 1,325 went to American exhibitors and 758 to foreigners, with Spain accounting for 107 of the medals. The Committee on Awards, whose president was former San Francisco Mayor Frank McCoppin, appointed 213 jurors to judge the thousands of exhibits. The major buildings of the California Midwinter International Exposition were clustered around the Grand Court of Honor whose general outline still exists today as the Music Concourse in Golden Gate Park.

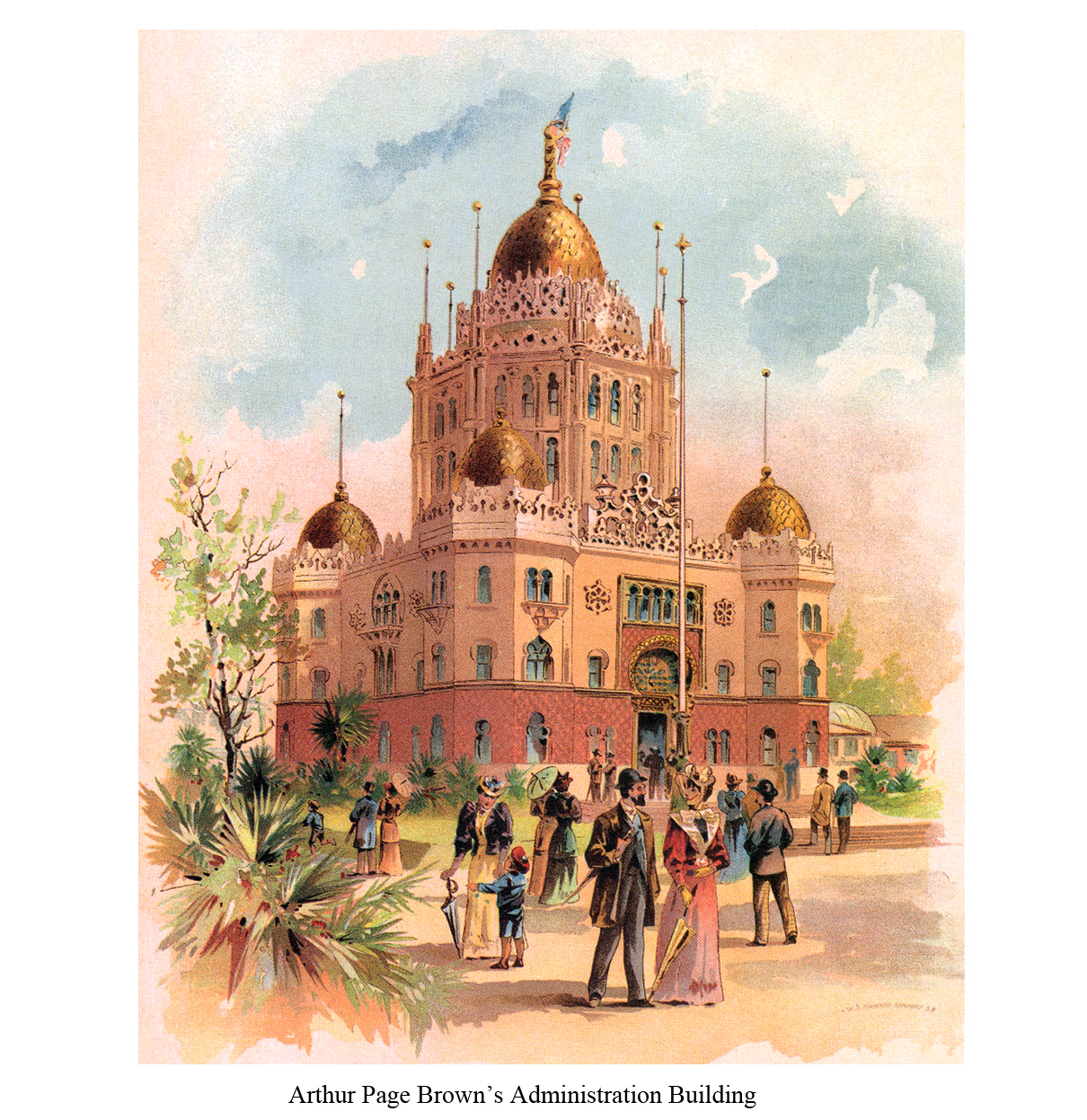

At the southwestern end of the court stood Arthur Page Brown's Administration Building, a storybook fantasy that conjured up visions of fairy-tale palaces. Its hexagonal tower, keyhole windows, and lacelike battlements inhabited an imaginative world far distant from the grandly sober and white buildings of the Chicago fair. Inside the building were the managers, clerks, and functionaries who looked after the daily business of the fair.

Facing this building on the northeastern end of the Court of Honor was Brown's Manufactures and Liberal Arts Building — a cavernous structure which was the largest ever built in California up until that time (225 feet wide, 462 feet long). Modeled on the Palais de l'Industrie in Paris, the Manufactures and Liberal Arts Building recalled the glory of the first French exposition universelle, held in 1855. The building was made up of two distinct parts: an interior of glass-and-iron vaulting, which allowed large amounts of natural light to brighten the interior, and an outer sheathing of simulated stone, which gave an effect of solidity and massiveness.(7) The Arabic horseshoe arch over the entranceway echoed the similarly shaped portals on the Administration Building across the concourse — Brown’s tribute to the coordinated planning of Daniel Burnham at the Chicago exposition for which the young California architect had designed the massive California Building. Here the fairgoers could see a full range of human ingenuity — from cut glass to corset stays, phonographs to flutes — arrayed before them.

Arthur Page Brown's Manufactures and Liberal Arts Building

On the southeast side of the Grand Court stood Edward Swain's Mechanical Arts Building. This colorful structure blended the architectures of the Near East, India, and the Slavic countries, with its minarets and onion domes soaring over ogival arches and intricate arabesques. Flags of the participating nations waved from the spires, and gave the building a festive international appearance. On display inside were the dynamos and large-scale engines that embodied the most current marvels of the Industrial Revolution. The best of Western technology housed in splendid palaces from faraway lands -- that was San Francisco's dream of the ideal world of the future.

Edward Swain's Mechanical Arts Building

(Click the image for a LIGHTBOX view)

On the northwest side of the Concourse stood the last of the major buildings of the Midwinter Fair: Samuel Newsom's Horticultural and Agricultural Building, and C. C. McDougal's Fine Arts Building. Newsom's structure, with its iron and glass dome and Romanesque colonnade, was dubbed "generally speaking, the California Mission Style," and recalled the California Building at the Chicago fair.

The glass dome was especially striking at night, when interior illumination made Newsom's creation glow like an immense jewel lit from within. The Horticultural and Agricultural Building housed an abundance of exotic plants, flowers, and even aquatic life. On one special day, snow was brought down from the Sierra and strewn throughout the corridors of the building to give the right backdrop for a special "sugaring-off" exhibition by the Vermont delegation.

It was here, in front of the Mechanical Arts Building, that the first automobile in San Francisco made its appearance.

The Fine Arts Building, located next to the Horticultural Building, was the most bizarre exhibition hall at the Midwinter Fair. Built in Egyptian Revival style by C. C. McDougal, the building was cursed with troubles from its inception. It was originally built to precisely rational specifications: 120 feet by 60 feet. But the clamor for exhibit space soon forced McDougal to add an annex, which added some 40 feet to the width. Nothing gives a clearer glimpse into the aesthetic sensibilities of turn of the century San Francisco than to read in the Official History of the California Midwinter International Exposition that "the [Fine Arts] building is simple in form and unpretentious in outline."' A pyramidal roof, projecting cornices surmounted by winged sphinxes, a recessed facade fronted by pseudo-Egyptian pillars, and all completely covered with imitation hieroglyphs To any observer today, the Fine Arts Building would undoubtedly appear both pretentious and slightly ridiculous: a "theme building" in the manner of amusement park structures. After the Midwinter Fair closed in July of 1894, this historical fantasy was formally dedicated as the M. H. de Young Memorial Museum, San Francisco's first municipal art museum. Plagued by structural problems from the outset — museum officials constantly complained of leaks which could never be fixed — and overshadowed by Louis Christian Mulgardt's Spanish Revival "annex" to the museum built in 1918, McDougal's Egyptian palace was badly damaged in the 1906 earthquake and eventually fell to the wrecker's ball in 1928.(9)

In the very center of the Midwinter Exposition stood a tower which, at first view, seemed stylistically out of context with the other structures of the Grand Court of Honor. Furthermore, it was the only one of the major buildings not designed by a local architect. Frenchman Leopold Bonet's Electrical Tower was an obvious descendant of the Eiffel Tower,(10) with its soaring, unadorned steel girders and its lofty observation platforms. The electric tower was the brainchild of diplomat and designer Leopold Bonet, the French commissioner to both the Chicago and the San Francisco expositions. Bonet, head of a construction firm in Chicago, had tried to interest the Chicago commissioners in the idea of constructing a tower on the fairgrounds there, but his proposal was rejected. When he learned of the proposed Midwinter Fair, he wisely changed his tactics.

Following Gustave Eiffel's lead, Bonet formed a private syndicate of investors who provided him with an initial capital of $5,000 to build his tower in San Francisco. Investors in the syndicate were then to receive a percentage of the profits from the concession. In fact, Bonet's $5,000 was the very "first money paid into the treasury of the Exposition on account of a concession.”(11)

Though the Bonet Tower was less than one third the size of the Eiffel Tower, it surpassed its Parisian counterpart in two respects. The Eiffel Tower was made of iron: a building material destined to give way to the greater structural advantages of steel. Bonet fashioned his tower of steel, making it the first structure of its kind in the United States. In addition, the Bonet Tower had more spectacular lighting effects. The Eiffel Tower had also been adorned with Thomas Edison's recent invention, the electrical light bulb, and even boasted searchlight powerful enough to allow one to read a newspaper by its light at a distance of one mile from the Tower itself. But the Bonet Tower entranced fairgoers with its own special magic. During the day, the Electrical Tower stood as the central symbol for the promise of modern technology: power in the service of humankind. But at night the lights of the Tower seemed to come alive. The girders were covered with interconnected strings of 3,200 incandescent light bulbs which were programmed to change by means of a coded metal cylinder. Diamonds, rosettes, crosses and circles flashed and winked out across the darkened girders. The Official History of the exposition reported that "One thousand of these were employed for outlining the tower, one thousand for the fixed decorative light effects, and twelve hundred in the changing geometrical designs." (12) And at the Tower's crown, "the most powerful searchlight in the world," shone across the young trees of the park, and illuminated the cross on Prayer Book Cross Hill. One commentator asserted that he could read a newspaper at midnight ten miles away by the light of the tower's beams -- a substantial improvement over the Eiffel Tower's searchlight, (13)

In the end, Bonet achieved his goals. The Tower made money as a concession and amply justified his faith in the ability of such an attraction to produce a profit. He had shown that Eiffel's crowning achievement could be, if not equaled, at least emulated, even in a remote and youthful American city such as San Francisco.

Bonet set one more precedent that would continue throughout San Francisco's history of hosting world's fairs. The Electrical Tower was what the French called a clou — a "spike" that gave an exposition a central, dominant structure. Other great American world's fairs — New York in 1853-4, Philadelphia in 1876, Chicago in 1893 — had their own striking and distinctive buildings. But none had had the spike that gave the world a memorable image of the dominant theme and meaning of the exposition. Eiffel's Tower was a self-conscious exclamation point to the Paris exposition universelle of 1889. Bonet's Tower served the same purpose for San Francisco in 1894, thereby creating a precedent for two later world's fairs: the Panama Pacific International Exposition with its Tower of Jewels, and the Golden Gate International Exposition's Tower of the Sun.(14)